What Are Three Catergories That Makeup Investments In Econ

Top 3 Theories of Investment – Discussed!

The post-obit points highlight the top three theories of investment in Macro Economics. The theories are: one. The Accelerator Theory of Investment 2. The Internal Funds Theory of Investment three. The Neoclassical Theory of Investment.

Theory of Investment # 1. The Accelerator Theory of Investment:

The accelerator theory of investment, in its simplest course, is based upon the nation that a particular amount of capital stock is necessary to produce a given output.

For case, a capital stock of Rs. 400 billion may be required to produce Rs. 100 billion of output. This implies a stock-still relationship between the capital stock and output.

Thus, 10 = Mt /Yt

where x is the ratio of Kt, the economy'south majuscule stock in time period t, to Yt, its output in lime period t. The relationship may also be written as

Kt = xYt …(i)

If 10 is abiding, the same relationship held in the previous menses; hence

Kt-1 = xYt-i

By subtracting equation (ii) from equation (i), we obtain

1000t –Thousandt-i = xYt.x Yt-1 = x(Yt-Yt-1) …(two)

Since net investment equals the difference between the capital stock in time period t and the majuscule stock in time menstruation t – ane, internet investment equals ten multiplied by the change in output from time period t – i to fourth dimension period t.

By definition, net investment equals gross investment minus upper-case letter consumption allowances or depreciation. If It represents gross investment in fourth dimension menses t and Dt represents depreciation in fourth dimension period t, net investment in time catamenia t equals It – Dt and

It-Dt = x (Yt – Yt-1) = x ∆ Y.

Consequently, internet investment equals x, the accelerator coefficient, multiplied by the change in output. Since x is assumed constant, investment is a function of changes in output. If output increases, internet investment is positive. If output increases more rapidly, new investment increases.

From an economic standpoint, the reasoning is straightforward. According to the theory, a item corporeality of capital is necessary to produce a given level of output. For case, suppose Rs. 400 billion worth of capital is necessary to produce Rs. 100 billion worth of output. This implies that x, the ratio of the economy's capital letter stock to its output, equals iv.

If amass demand is Rs. 100 billion and the capital stock is Rs. 400 billion, output is Rs. 100 billion. So long equally aggregate demand remains at the Rs. 100 billion level, net investment will exist zero, since there is no incentive for firms to add together to their productive chapters. Gross investment, withal, volition exist positive, since firms must replace found and equipment that is deteriorating.

Suppose aggregate need increases to Rs. 105 billion. If output is to increment to the Rs. 105 billion level, the economy's capital stock must increase to the Rs. 420 billion level. This follows from the supposition of a fixed ratio, ten, between uppercase stock and output. Consequently, for product to increment to the Rs. 105 billion level, net investments must equal Rs. 20 billion, the amount necessary to increment the capital letter stock to the Rs. 420 billion level.

Since ten equals iv and the modify in output equals Rs. 5 billion, this amount, Rs. twenty billion, may exist obtained straight by multiplying x, the accelerator coefficient, by the modify in output. Had the increase in output been greater, (net) investment would have been larger, which implies that (internet) investment is positively related to changes in output.

In this crude grade, the accelerator theory of investment is open to a number of criticisms.

Outset, the theory explains cyberspace but not gross investment. For many purposes, including the determination of the level of amass demand, gross investment is the relevant concept.

Second, the theory assumes that a discrepancy between the desired and actual capital stocks is eliminated within a single flow. If industries producing upper-case letter appurtenances are already operating at full chapters, information technology may not exist possible to eliminate the discrepancy within a unmarried flow. In fact, even if the industries are operating at less than total capacity information technology may be more economical to eliminate the discrepancy gradually.

Third, since the theory assumes no backlog chapters, we would not wait it to be valid in recessions, since they are characterized by backlog capacity. Based on the theory, cyberspace investment is positive when output increases. Simply if excess chapters exists, we would look fiddling or no net investment to occur, since net investment is made in social club to increase productive capacity.

Fourth, the accelerator theory of investment, or acceleration principle, assumes a stock-still ratio betwixt capital and output. This assumption is occasionally justified, but well-nigh firms can substitute labor for capital, at least inside a limited range. Equally a upshot, firms must have into consideration other factors, such as the interest rate.

5th, fifty-fifty if at that place is a fixed ratio betwixt capital and output and no excess capacity, firms will invest in new constitute and equipment in response to an increment in aggregate demand but if demand is expected to remain at the new, college level. In other words, if managers await the increase in demand to be temporary, they may maintain their present levels of output and heighten prices (or permit their orders pile up) instead of increasing their productive chapters and output through investment in new plant and equipment.

Finally, if and when an expansion of productive chapters appears warranted, the expansion may not exist exactly that needed to meet the electric current increase in need, but one sufficient to meet the increase in demand over a number of years in the futurity.

Piecemeal expansion of facilities in response to short-run increases in demand may exist uneconomical or, depending upon the industry, even technologically impossible. A steel house cannot, for example, add half a boom furnace. In view of these and other criticisms of the accelerator theory of investment, it is not surprising that early on attempts to verify the theory were unsuccessful.

Over the years, more flexible versions of the accelerator theory of investment have been developed. Different the version of the accelerator theory but presented, the more flexible versions assume a discrepancy between the desired and actual capital stocks which is eliminated over a number of periods rather than in a single menstruum. Moreover, it is assumed that the desired capital stock, G*, is determined by long-run considerations. As a consequence

![]()

where Grandt is the bodily capital stock in fourth dimension period t, Kt-i is the actual capital stock in time period t-1, Chiliadt* is the desired capital stock, and λ is a abiding between 0 and 1. The equation suggests that the actual change in the capital stock from fourth dimension menstruum t – 1 to time catamenia t equals a fraction of the departure between the desired capital stock in time period t and the actual majuscule stock in time period t—1. If λ were equal to i, as assumed in the initial statement of the accelerator theory, the bodily capital stock in time period t equals the desired upper-case letter stock.

Since the alter in the capital stock from fourth dimension period t – 1 to time menstruation t equals net investment, It – Dt we have

![]()

Consequently, net investment equals A multiplied by the difference between the desired capital stock in time flow t and the actual capital stock in time period t- 1. The relationship, therefore, is in terms of net investment.

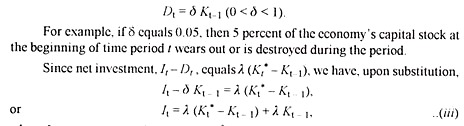

To account for gross investment, it is common to assume that replacement investment is proportional to the bodily capital stock. Thus, nosotros assume that replacement investment in lime period t, Dt equals a constant δ multiplied by the capital stock at the end of time period t-1, Kt-one, or

where It represents gross investment, Gt* the desired capital stock, and Kt. , the bodily upper-case letter stock in time period t-i. Thus, gross investment is a part of the desired and actual capital letter stocks.

Finally, according to the accelerator model, the desired upper-case letter stock is determined past output. Yet, rather than specifying that the desired capital stock is proportional to a single level of output, the desired capital stock is commonly specified every bit a function of both current and past output levels. Consequently, the desired uppercase stock is determined by long-run considerations.

In contrast to the crude accelerator theory, much empirical evidence exists in support of the flexible versions of the accelerator theory.

Theory of Investment # two. The Internal Funds Theory of Investment:

Under the internal funds theory of investment, the desired majuscule stock and, hence, investment depends on the level of profits. Several different explanations have been offered. Jan Tinbergen, for example, has argued that realized profits accurately reflect expected profits.

Since investment presumably depends on expected profits, investment is positively related to realized profits. Alternatively, it has been argued that managers take a decided preference for financing investment internally.

Firms may obtain funds for investment purposes from a variety of sources:

(1) Retained earnings,

(ii) Depreciation expense (funds ready aside every bit found and equipment depreciate),

(three) Various types of borrowing, including auction of bonds,

(4) The sale of stock.

Retained earnings and depreciation expense are sources of funds internal to the firm; the other sources are external to the firm. Borrowing commits a house to a series of fixed payments. Should a recession occur, the business firm possibly unable to meet its commitments, forcing it to borrow or sell stock on unfavorable terms or even forcing it into defalcation.

Consequently, firms may be reluctant to borrow except under very favourable circumstances.

Similarly, firms may be reluctant to enhance funds past issuing new stock. Direction, for case, is oftentimes concerned virtually its earnings record on a per share basis. Since an increase in the number of shares outstanding tends to reduce earnings on a per share ground, management may be unwilling to finance investment by selling stock unless the earnings from the project clearly commencement the effect of the increase in shares outstanding.

Similarly, management may fear loss of command with the sale of boosted stock. For these and other reasons, proponents of the internal funds theory of investment argue that firms strongly prefer to finance investment internally and that the increased availability of internal funds through higher profits generates additional investment. Thus, according to the internal funds theory, investment is determined past profits.

In dissimilarity, investment, according to the accelerator theory, is determined by output. Since the two theories differ with regard to the determinants of investment, they also differ with regard to policy. Suppose policy makers wish to implement programs designed to increase investment.

According to the internal funds theory, policies designed to increase profits directly are likely to be the nigh effective. These policies include reductions in the corporate income taxation charge per unit, assuasive firms to depreciate plant and equipment more rapidly, thereby reducing their taxable income, and assuasive investment tax credits, a device to reduce firms' taxation liabilities.

On the other hand, increases in government purchases or reductions in personal income tax rates will take no directly effect on profits, hence no direct event on investment. To the extent that output increases in response to increases in government purchases or revenue enhancement cuts, profits increase. Consequently, there will be an indirect effect on investment.

In dissimilarity, nether the accelerator theory of investment, policies designed to influence investment directly nether the internal funds theory will be ineffective. For example, a reduction in the corporate tax charge per unit will have niggling or no outcome on investment considering, under the accelerator theory, investment depends on output, non the availability of internal funds.

On the other paw, increases in government purchases or reductions in personal income tax rates will exist successful in stimulating investment through their impact on aggregate demand, hence, output.

Before turning to the neoclassical theory, nosotros should note in fairness to the proponents of the internal funds theory that they recognize the importance of the relationship between investment and output, especially in the long run. At the same time, they maintain that internal funds are an important determinant of investment, peculiarly during recessions.

Theory of Investment # 3.The Neoclassical Theory of Investment:

The theoretical basis for the neoclassical theory of investment is the neoclassical theory of the optimal aggregating of capital. Since the theory is both long and highly mathematical, we shall not attempt to outline it. Instead, nosotros shall briefly examine its principal results and policy implications.

According to the neoclassical theory, the desired upper-case letter stock is determined by output and the cost of capital letter services relative to the cost of output. The price of upper-case letter services depends, in turn, on the price of majuscule appurtenances, the interest rate, and the tax treatment of business income. As a consequence, changes in output or the cost of capital services relative to the toll of output modify the desired uppercase stock, hence, investment.

Every bit in the case of the accelerator theory, output is a determinant of the desired majuscule stock. Thus, increases in regime purchases or reductions in personal income tax rates stimulate investment through their impact on aggregate need, hence, output. As in the instance of the internal funds theory, the tax handling of business income is important.

According to the neoclassical theory, however, business organisation taxation is important because of its result on the cost of capital services, not considering of its upshot on the availability of internal funds. Fifty-fifty so, policies designed to modify the tax treatment of business income bear on the desired majuscule stock and, therefore, investment.

In contrast to both the accelerator and internal funds theories, the interest rate is a determinant of the desired capital stock. Thus, monetary policy, through its effect on the interest rate, is capable of altering the desired capital stock and investment. This was non the example in regard to the accelerator and internal funds theories.

The policy implications of the various theories of investment differ. It is of import, therefore, to determine which theory best explains investment behaviour. We now plough to the empirical evidence. There is considerable disagreement concerning the validity of the accelerator, internal funds, and neoclassical theories of investment.

Much of the disagreement arises considering the various empirical studies accept employed different sets of data. Consequently, several economists have tried to examination the various theories or models of investment using a common set of data.

At the aggregate level, Peter K. Clark considered various models including an accelerator model, a modified version of the internal funds model, and two versions of the neoclassical model. Based on quarterly data for 1954-73, Clark ended that the accelerator model provides a amend explanation of investment behaviour than the alternative models.

At the manufacture level, Dale West. Jorgenson, Jerald Hunter, and 1000. Ishag Nadiri tested four models of investment behavior: an accelerator model, two versions of the internal funds model, and a neoclassical model. Their study covered 15 manufacturing industries and was based on quarterly data for 1949-64. Jorgenson, Hunter, and Nadiri found, like Clark, that the accelerator theory is a ameliorate explanation of investment behavior than cither of the two versions of the internal funds models. But unlike Clark, they concluded that the neoclassical model was amend than the accelerator model.

At the firm level, Jorgenson and Calvin D. Siebert tested a number of investment models, including an accelerator model, an internal funds model, and two versions of the neoclassical model. The study was based on information for fifteen large corporations and covered 1949-63. Jorgenson and Siebert concluded that the neoclassical models provided the all-time explanation of investment behavior and the internal funds model the worst.

Their conclusions arc consistent with those of Jorgenson, Hunter and Nadiri and with regard to the internal funds theory, with those of Clark. Clark concluded, however, that the accelerator model was better than the neoclassical model.

In brusk, these studies suggest that the internal funds theory does not perform too as the accelerator and neoclassical theories at all levels of aggregation. The evidence, however, is conflicting with regard to the relative performance of the accelerator and neoclassical models, with the testify favoring the accelerator theory at the aggregate level and the neoclassical model at other levels of aggregation.

In an important survey commodity, Jorgenson has ranked different variables in terms of their importance in determining the desired capital letter stock. Jorgenson divided the variables into three main categories: capacity utilization, internal finance, and external finance. Capacity utilization variables include output and the human relationship of output to chapters. Internal finance variables include the flow of internal funds; external finance variables include the interest rate. Jorgenson found chapters variables to be the most important determinant of the desired capital letter stock.

He likewise found external finance variables to be of import, although definitely subordinate to capacity utilization variables. Finally, Jorgenson institute that internal finance variables play lilliputian or no function in determining the desired capital stock. This result is, at beginning glance, surprising. Later on all, there is a strong, positive correlation betwixt investment and profits. Firms do invest more when profits are high.

However, in that location is also a strong, positive correlation between profits and output. When profits are loftier, firms are normally operating at or close to full capacity, thereby providing an incentive for firms to add together to their productive capacity. Indeed, when both output and profits are included equally determinants of investment, the profits variable loses all or about all of its explanatory-power.

Jorgenson'due south conclusions in regard to the importance of internal funds are, of course, consistent with the results of the tests of alternative investment models. Nosotros conclude, therefore, that the marginal funds model is inadequate as a theory of investment behavior.

Jorgenson'southward conclusion in regard to the capacity utilization variables lends some support to the proponents of the accelerator model. Simply he finds external finance variables to be of importance in determining the desired majuscule stock, which suggests that the neoclassical model is the appropriate theory of investment behavior, since it includes both output and the price of capital letter services every bit determinants of the desired upper-case letter stock.

Source: https://www.economicsdiscussion.net/investment/theories-investment/top-3-theories-of-investment-discussed/14585

Posted by: ramosbuttle.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Are Three Catergories That Makeup Investments In Econ"

Post a Comment